The Death of Kremlinology: What Russia’s 2025 Victory Day Parade Revealed

As Putin sidelines officials and spotlights foreign guests, the 2025 Victory Day parade exposes a Russia far different from the one we knew before.

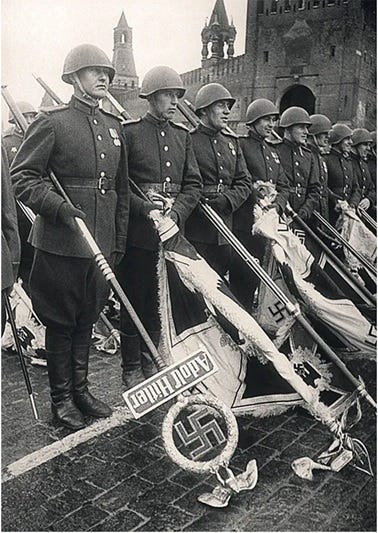

Once upon a time, you could read the Soviet Union like a cryptic script. Who stood closest to the General Secretary at the May 9 parade? Who disappeared from the balcony? Which general’s cap was slightly off-center? Kremlinology—part science, part superstition—existed because the Soviet system, for all its brutality, had rules, factions, and structure. But in 2025, that discipline lies buried beneath the ruins of the old order.

What replaced it? Something simpler, murkier, and more personal: Putinology.

This year’s Victory Day parade in Moscow wasn’t about who surrounded Putin—it was about who didn’t. The domestic power structure, once carefully arranged and endlessly analyzed, barely registered. The cameras focused instead on the foreign guests in the stands: Xi Jinping, Lula da Silva, Nicolás Maduro, and others. Their presence was a message—not of ideological unity, but of mutual utility.

Shoigu’s quiet demotion said more than any speech. Once the centerpiece in full military regalia, this year he stood back in a business suit, no longer defense minister. Under the Soviet system, that shift would have set alarm bells ringing. Today, it barely caused a ripple.

Even North Korea, supposedly one of Russia’s few remaining true allies, seems to be drawing its own red lines. Support, yes—but limited. The old image of tight-knit anti-Western unity is cracking.

“The Soviet Union, for all its brutality, operated through committees, ideology, and structure,” says Mark N. Katz, professor emeritus at George Mason University and a longtime Kremlin watcher. “Putin’s Russia is built on improvisation, loyalty, and instinct. Putin does not manage a system—rather, Putin is the system.”

That’s the central shift. Kremlinologists once decoded a bureaucracy. Putinologists now track a man. There’s no Politburo, no party congresses, no ideology to speak of—just a ruler, a stage, and a rotating cast of guests.

Katz also points to something deeper. During the Cold War, the U.S. built entire institutions to understand the Kremlin—academic centers, funding, intelligence networks. “Today, the intellectual spotlight has moved elsewhere—toward China, the Middle East, and emerging technologies,” he notes. “Russia is no longer the center of analytical gravity in American academia.”

The parade, like the country it represents, goes through the motions. Soldiers march. Flags fly. But the subtext is no longer strategy—it’s spectacle. Putin remains at the center. Everything else is just choreography.